- Home

- Margaret Atwood

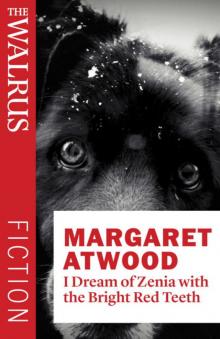

I Dream of Zenia with the Bright Red Teeth

I Dream of Zenia with the Bright Red Teeth Read online

I Dream of Zenia with the Bright Red Teeth

Margaret Atwood

Long ago, when they were all a lot younger, Zenia stole a man from each of them. Then she died. Now she’s come back. Or has she? There’s a lot more than one kind of ghost.

Margaret Atwood revisits her classic characters from The Robber Bride. This story first appeared in the July/August 2012 issue of The Walrus magazine.

Margaret Atwood

I DREAM OF ZENIA WITH THE BRIGHT RED TEETH

“I HAD A DREAM about Zenia last night,” says Charis.

“Who?” says Tony.

“Oh, crap!” says Roz. Charis’s black and white mystery-mix dog, Ouida, has just smeared her muddy paws down the front of Roz’s new coat. The coat is orange, perhaps not the best choice. Charis claims that Ouida has special perceptive powers, and that her paw smearings are messages. What is Ouida trying to say to me? wonders Roz. You look like a pumpkin?

It’s autumn. The three of them are shuffling through the dry leaves in the ravine, taking their weekly walk. It’s a pact they’ve made: to get more exercise, to improve their cellular autophagic rates. Roz has read about this in one of the health magazines in the dentist’s waiting room: bits of your cells eat other bits that are diseased or dying. This intracellular cannibalism is said to help you live longer.

“What do you mean, ‘crap’?” says Charis. With her long white crinkly face and her long white crinkly hair, she’s more sheeplike than ever. Or more like an angora goat, thinks Tony, who prefers the specific to the general. That inward, ruminative look.

“I didn’t mean your dream,” says Roz. “I meant Ouida. Sit, Ouida!”

“She likes you,” says Charis fondly.

“Sit, Ouida!” says Roz with some annoyance. Ouida bounds away.

“She’s so full of energy!” says Charis. She’s been a dog owner for just three months, and already every irritating thing that mutt does is beyond adorable. You’d think she’d given birth to it.

“Awesome!” says Tony, who sometimes echoes her students. She’s now a professor emeritus, but she still teaches one graduate seminar, “Early Technologies of War.” They’ve just done the scorpion bombs, always popular, and have now reached the composite short bows of Attila the Hun, with their bone stiffeners. “Zenia! Unfuckingbelievable! Did she ooze out of a tomb?”

She peers up at Charis through her round glasses. In her twenties, Tony looked like a pixie. She still does, but a freeze-dried pixie. More papery.

“When was it she died?” says Roz. “I’ve lost track. Isn’t that awful?”

“Shortly after 1989,” says Tony. “Or 1990. When the Berlin Wall was coming down. I’ve got a piece of it.”

“You think it’s real?” says Roz. “People were chipping cement off anything then! It’s like the True Cross, or saints’ finger bones, or…or fake Rolex watches.”

“It’s a memento,” says Tony. “They don’t have to be real.”

“Time isn’t the same in dreams,” says Charis, who likes reading about what’s going on in her head when she isn’t awake, though sometimes, thinks Roz, it’s hard to tell the difference. “In dreams, nobody’s dead, really. That’s what the man who…he says, in dreams the time is always Now.”

“That’s not too comforting,” says Tony. She likes things to stay in their categories. Pens in this jar, pencils in that. Vegetables on the right side of the plate, meat on the left. The living here, the dead over there. Too much osmosis, too much wavering — it can be dizzying.

“What was she wearing?” Roz asks. Zenia had dressed stunningly, back when she was alive. She’d favoured luscious colours like sepia and plum. She’d had glamour, whereas Roz has only ever had class.

“Leather,” says Tony. “With a silver-handled whip.”

“Just a sort of shroud thing,” says Charis. “It was white.”

“I can’t see her in white,” says Roz.

“We didn’t use a shroud,” says Tony. “For the cremation. We chose one of her own dresses, remember? Sort of a cocktail dress. Dark.” Zenia spelled backwards is Ainez, a Spanish-sounding name. There was definitely a Spanish element to Zenia: as a singer, she’d have been a contralto.

“The two of you made that decision,” says Roz. “I’d have put her in a sack.” She had proposed the sack idea, but Charis had argued for proper vestments: otherwise, Zenia might be resentful and hang around.

“Okay, maybe not a shroud,” says Charis. “More like a nightgown. Sort of floaty.”

“Did it glow?” says Tony with interest. “Like ectoplasm?”

“What about the shoes?” says Roz. Shoes once played a major part in Roz’s life — expensive shoes with high heels — but toe gnarling and bunions have put paid to that. Walking shoes can be very nice as well, however. She might get those new every-toe-separate kind. They make you look like a frog, but they’re supposed to be very comfortable.

“Of course, it was painted gauze, really,” says Tony. “They stuffed it up their noses.”

“What in heck are you talking about?” says Roz.

“Her feet were not the point,” says Charis. “The point was…”

“I suppose she had fangs dripping blood,” says Tony. That would be the sort of overacting Zenia would go in for. Red contact lenses, hissing, claws, the works.

Charis ought to stop watching vampire films at night. It’s bad for her; she’s so impressionable. Both Tony and Roz think this, so they go over to Charis’s house on vampire nights so at least she won’t be watching alone. Charis makes mint tea and popcorn for them, and they sit on her sofa like teenagers, cramming popcorn into their mouths, feeding the occasional handful to Ouida, glued to the screen as the music shifts to eerie, and eyes redden or yellow, and teeth elongate, and blood spurts like pizza sauce over everything in sight. Whenever wolves are audible, Ouida howls.

Why are the three of them indulging in these adolescent pursuits? Is it some kind of grisly substitute for diminishing sex? They seem to have thrown away all the maturity and experience and wisdom they've collected like Air Miles over their middle years; just tossed them out, in favour of irresponsible buttery and salty munching and cheesy, adrenaline-soaked time wasting. After these curious orgies, Tony spends days picking white hairs off her cardigans — some from Ouida, some from Charis. “Have a nice evening?” West would ask, and Tony would say they’d just done a lot of boring girl talk, as usual. She doesn’t want West to feel he’s missed out.

Things are getting out of hand: Tony catches herself channelling this opinion at least once a day. The crazed weather. The vicious, hate-filled politics. The myriad glass high-rises going up like 3-D mirrors, or siege engines. The municipal garbage collection: Who can keep all those different-coloured bins straight? Where to put the clear plastic food containers, and why isn’t the little number on the bottom a reliable guide?

And the vampires. You used to know where you stood with them — smelly, evil, undead — but now there are virtuous vampires and disreputable vampires, and sexy vampires and glittery vampires, and none of the old rules about them are true anymore. Once you could depend on garlic, and on the rising sun, and on crucifixes. You could get rid of the vampires once and for all. But not anymore.

“Actually, not fangs as such,” says Charis. “Though her teeth were kind of pointy, come to think of it. And sort of pink. Ouida, stop that!”

Now Ouida is dashing around and barking: being in the ravine and off the leash excites her. She likes to nose under fallen logs and dodge behind bushes, evading the moment of recapture and hiding her — what to call them? Charis disapproves of crass words like “shit.” Roz has

offered “poop,” but Charis rejected it as too babyish. Her alimentary canal products? Tony has suggested. No, that sounds too coldly intellectual, said Charis. Her Gifts to the Earth.

Hiding her Gifts to the Earth, then, while Charis dithers along behind, clutching a plastic disposal bag (such bags are almost never used by Charis, because she often cannot locate the Gifts) and calling weakly at intervals, as she is doing at present: “Ouida! Ouida! Come here! Good girl!”

“So there she was,” says Tony. “Zenia. In your dream. Then what?”

“You think this is stupid,” says Charis. “But anyway. She wasn’t menacing or anything. In fact, she seemed kind of friendly. She had a message for me. What she said was, Billy’s coming back.”

“News must travel slowly in the afterlife,” says Tony, “because Billy’s already come back, right?”

“Not exactly back,” says Charis primly. “I mean, we’re not…he’s only next door.”

“Which is already too close for comfort,” says Roz.

“Why the heck you ever rented to that deadbeat I just don’t get.”

LONG AGO, when they were all a lot younger, Zenia had stolen a man from each of them. From Tony, she’d stolen West, who did however think better of it — or that is Tony’s official version to herself — and is safely rooted in Tony’s house, fooling with his electronic music system and getting deafer by the minute. From Roz, she’d stolen Mitch, not exactly hard, since he’d never been able to keep it zipped; but then, after emptying not only his pockets but what Charis called his psychic integrity, Zenia had dumped him, and he’d drowned himself in Lake Ontario. He’d worn a life jacket, and he’d made it look like a sailing accident, but Roz had known.

She’s over that by now, or as much as a girl can ever be over it, and she has a much nicer husband called Sam, who’s in merchant banking and more suitable, with a better sense of humour. But still, it’s a scar. And it hurt the children; that’s the part she can’t forgive, despite the shrink she went to in an effort to wipe the slate. Not that there’s any percentage in not forgiving a person who’s no longer alive.

From Charis, Zenia had stolen Billy. That was perhaps the cruellest theft, think Tony and Roz, because Charis was so trusting and defenceless, and let Zenia into her life because Zenia was in trouble, and was a battered woman, and had cancer, and needed someone to take care of her, or that was her story — a shameless fabrication in every part. Charis and Billy were living on the Island then, in a little house that was more like a cottage. They kept chickens. Billy built the coop himself; being a draft dodger, he didn’t exactly have a steady job.

There wasn’t all that much room in the cottage for Zenia, but Charis made room, being hospitable and wanting to share, the way people were on the Island in those days, and in the dodger communities. There was an apple tree; Charis made apple cakes, and other baked items as well, with the eggs. She was so happy, and also pregnant. And the next thing you knew, Billy and Zenia had gone off together and all the chickens were dead. They’d had their throats cut with the bread knife. It was just so mean.

Why had Zenia done it? All of it? Why do cats eat birds? was Roz’s unhelpful answer. Tony thought it was an exercise in power. Charis was sure there was a reason, embedded somewhere in the workings of the universe, but she wasn’t sure what it could be.

Roz and Tony each ended up with a man in residence, despite Zenia’s best ruination efforts, but Charis didn’t. That was because she’d never achieved closure, was Roz’s theory. She couldn’t find anyone ditzy enough, was Tony’s. But less than a month ago, who should turn up but that long-lost schmuck of a Billy, and what did Charis do but rent him the other half of her duplex? It’s enough to make you tear your hair out by its tiny grey roots, thinks Roz, who still gets hers touched up every two weeks. A nice chestnut colour, not vivid. The complexion can get washed out if you go too bright.

CHARIS’S DUPLEX is a whole other story. Distant cousins should never die, thinks Tony; or if they do, they should never leave their money to kindly fools like Charis.

Because, now that Charis is no longer an ex–flower child and erstwhile dabbler in chicken raising, living on day-old bread and cat food and God knows what else in a badly insulated summer cottage on the Island, facing an increasingly impoverished and eventually hypothermic old age and fighting off her grown-up Ottawa bureaucrat of a daughter’s attempts to move her into a facility; because Charis is no longer an old street bat in training but is worth solid cash, Billy has come back into her life as if teleported.

Not that the distant cousin left a regal fortune, but she’d left enough so that Charis could move off the Island. It was getting too genteel for her anyway, she said, what with the renovations and the snobby people moving in, and she no longer felt really accepted there. Enough to stave off the facility fate and the day-old bread. Enough to buy a house.

Charis could have chosen a detached home, but she was maybe losing track of things sometimes — that was how she put it, causing Tony to say “No shit!” privately to Roz over the phone — and the concept was that she would live in one half of the duplex and rent the other half to someone who was, well, better with tools than she was, and she would trade that person lower rent for maintenance and repairs. Skill trading was so much less mercenary than charging market value rent, didn’t Roz and Tony feel that?

They didn’t, but Charis had brushed their counsel aside and put an offer up on Craigslist, with (Tony thinks) maybe a little too much description of herself and her tastes, all of which (Roz thinks) amounted to an open invitation to an unscrupulous prick like Billy. And presto, all of a sudden, there he was.

OUDIA DOES NOT LIKE BILLY. She growls at him. Which is some comfort, as Charis pays more attention to Ouida’s opinions now than to those of anyone else, including her two oldest friends.

It was Tony and Roz who’d given Ouida to Charis. Now that Charis is living in Parkdale — a location rapidly gentrifying, says Roz, who keeps an eye on real estate prices, and Charis will do well in the long run, but the gentrification is far from complete, and you never know what you might run into on the street, not to mention the drug dealers. Also, says Tony, Charis is such an innocent; she has no instinct for ambushes. And she doesn’t like to drive; she prefers to ramble about on foot in the wilder places of the city, ravines and High Park and such, communing with plant spirits. Or whatever the heck she thinks she’s doing, says Roz, and let’s just hope she doesn’t decide the Poison Ivy Fairy is her new best friend.

Neither of them wants to read about Charis in the paper. “Elderly Woman Mugged Under Bridge.” “Harmless Eccentric Found Battered.” A dog is a deterrent, and Ouida is a terrier blend, maybe with some border collie, a bright dog at any rate, they’d concluded as they were filling out the rescue dog papers. And with a little training…

Well, said Tony, after Ouida had been installed for a month. That was the weak link in the plan: Charis couldn’t train a banana. “But Ouida is very loyal,” said Roz. “I’d bet on Ouida in a pinch. She’s a good growler.”

“She growls at mosquitoes,” said Tony gloomily. As a historian, she has no faith in so-called predictable outcomes.

Ouida is named after a self-dramatizing novelist of the nineteenth century; she’d been a devoted lover of dogs, so what better name for Charis’s new pet? said Tony, who’d done the naming. Roz and Tony suspect that Charis sometimes thinks Ouida the dog actually is Ouida the self-dramatizing novelist, since Charis believes in recycling, not only for bottles and plastics but also for psychic entities. She once said defensively that Prime Minister Mackenzie King was convinced his dead mother had reincarnated in his Irish terrier, and nobody found that strange at the time. Tony refrained from commenting that nobody found it strange at the time because nobody knew about it at the time. But they’d found it plenty strange afterwards.

Once Roz gets home from their walk, she calls Tony on her cell. “What are we going to do?” she asks.

“About Zenia?”

says Tony.

“About Billy. The man’s a psychopath. He murdered those chickens!”

“Chicken murdering is a public service,” says Tony. “Somebody’s got to do it, or we’d be six feet deep in hens.”

“Tony. Be serious.”

“What can we do?” says Tony. “She’s not underage, we’re not her mother. She’s already getting that moony woo-woo look.”

“Maybe I’ll hire a detective. See what kind of record Billy’s got. Before he buries her in the garden.”

“That house hasn’t got a garden,” says Tony. “Only a patio. He’ll have to use the cellar. Stake out the hardware store, see if he buys any pickaxes.”

“Charis is our friend!” says Roz. “Don’t make jokes about this!”

“I know,” says Tony. “I’m sorry. I only make jokes when I don’t know what to do.”

“I don’t know what to do either,” says Roz.

“Pray to Ouida,” says Tony. “She’s our last line of defence.”

THEIR REGULAR WALKS are on Saturdays, but this is a crisis, so Roz fixes lunch for Wednesday.

The three of them used to eat at the Toxique, back in the days of Zenia. Queen Street West was edgier then: more green hair, more black leather, more comic book stores. Now the mid-scale clothing chains have moved in, though there are still some residual tattoo joints and button shops, and the Condom Shack is soldiering on. The Toxique is long gone, however. Roz settles for the Queen Mother Cafe. A little elderly and battered, but comfy, like the three of them.

Or like the three of them used to be. Today, however, Charis is ill at ease. She fiddles with her vegetarian pad Thai and keeps looking out the window, where Ouida is impatiently waiting, roped to a bicycle stand.

“When’s the next vampire night?” says Roz. She’s just come from the dentist and is having trouble eating, because of the freezing. Her teeth are going the way of her high-heeled shoes, and for the same reasons: crumbling and pain. And the expense! It’s like shovelling money into her open mouth. On the bright side, dentistry is far more pleasant than it used to be. Instead of writhing and sweating, Roz puts on dark glasses and earphones and listens to New Age dingle music, borne away on a wave of sedatives and analgesics.

Surfacing

Surfacing Hag-Seed

Hag-Seed Oryx and Crake

Oryx and Crake The Heart Goes Last

The Heart Goes Last The Handmaid's Tale

The Handmaid's Tale Lady Oracle

Lady Oracle Good Bones and Simple Murders

Good Bones and Simple Murders The Robber Bride

The Robber Bride Life Before Man

Life Before Man Alias Grace

Alias Grace The Blind Assassin

The Blind Assassin Cat's Eye

Cat's Eye The Testaments

The Testaments The Penelopiad

The Penelopiad MaddAddam

MaddAddam Dancing Girls & Other Stories

Dancing Girls & Other Stories On Writers and Writing

On Writers and Writing Selected Poems II (1976-1986)

Selected Poems II (1976-1986) Wilderness Tips

Wilderness Tips Dearly

Dearly The Tent

The Tent Bluebeard's Egg

Bluebeard's Egg The Edible Woman

The Edible Woman The Penelopiad: The Myth of Penelope and Odysseus

The Penelopiad: The Myth of Penelope and Odysseus Good Bones

Good Bones I Dream of Zenia with the Bright Red Teeth

I Dream of Zenia with the Bright Red Teeth Circle Game

Circle Game Choke Collar: Positron, Episode Two

Choke Collar: Positron, Episode Two Stone Mattress: Nine Tales

Stone Mattress: Nine Tales The MaddAddam Trilogy

The MaddAddam Trilogy Stone Mattress

Stone Mattress Power Politics

Power Politics MaddAddam 03 - MaddAddam

MaddAddam 03 - MaddAddam I’m Starved for You (Kindle Single)

I’m Starved for You (Kindle Single) Murder in the Dark

Murder in the Dark In Other Worlds

In Other Worlds Dancing Girls

Dancing Girls Moral Disorder

Moral Disorder